understanding the odds of multiple-choice guessing and when to use it to your advantage

w. jonas reger

abstract

this simulation study explores the efficacy of random guessing in multiple-choice exams, focusing on the impact of exam modifications. examining a scenario where a teacher alters an advanced college course exam, the investigation reveals a surprising decrease in scores attributed to increased choices per question. the central limit theorem plays a crucial role, highlighting reduced variability in test scores as the number of questions increases. visualized through monte carlo simulation, the cumulative distribution of scores underscores the diminishing chance of achieving high scores with an escalating number of questions, offering insights for educators and strategic perspectives for students.

unveiling the efficacy of random guessing in multiple-choice exams

have you ever wondered about the effectiveness of making random guesses on multiple-choice exams? it's a common advice students receive when unsure about an answer. after all, some chance from guessing is better than no chance form not answering, but let's delve deeper into how well this strategy actually works in different exam scenarios.

imagine a scenario where a teacher, concerned that too many students are performing well, decides to modify an advanced college course exam for 100 students. initially, the exam consists of 28 multiple-choice questions, each with three choices. the teacher finds that the scores are still high, so the exam is revamped to include only four harder questions, but now with five choices each. surprisingly, the scores drop. how does randomly guessing on these two exams compare, and what insights can we gain?

why do you think the scores dropped?

decoding the impact of random guessing and the intricacies of exam score variability

contrary to intuition, randomly guessing on the second exam doesn't necessarily lead to higher scores. the decrease in scores can be attributed to the increase in the number of choices per question. however, if both exams had the same number of choices per question, the average scores wouldn't differ significantly. the key factor here is the reduction in variability in possible test scores as the number of questions increases, a phenomenon known as the central limit theorem.

let's break it down. if a class entirely relied on random guessing for both exams, the average scores would be similar. high scores on the first exam might indicate that it was slightly easier, and students were adequately prepared. the score drop in the second exam could suggest either insufficient preparation or excessive difficulty. in either case, random guessing was likely used in the second exam due to a lack of familiarity with the material.

a crucial change between the two exams is the combination of a reduced number of questions, increased number of options, and increased content difficulty in the second exam. this introduces more variability in possible scores for students resorting to random guessing, offering a wider range of potential outcomes – from very low to very high scores.

now, how do randomly guessed scores compare to those of students who prepared for the exam? the increased variability in random guessing scores makes scenarios like a student scoring 50% after 30 hours of studying while another student scores more than 50% with no preparation more common, highlighting the impact of question difficulty and the benefits of random guessing.

examining exam scores by insights from monte carlo simulation and central limit theorem

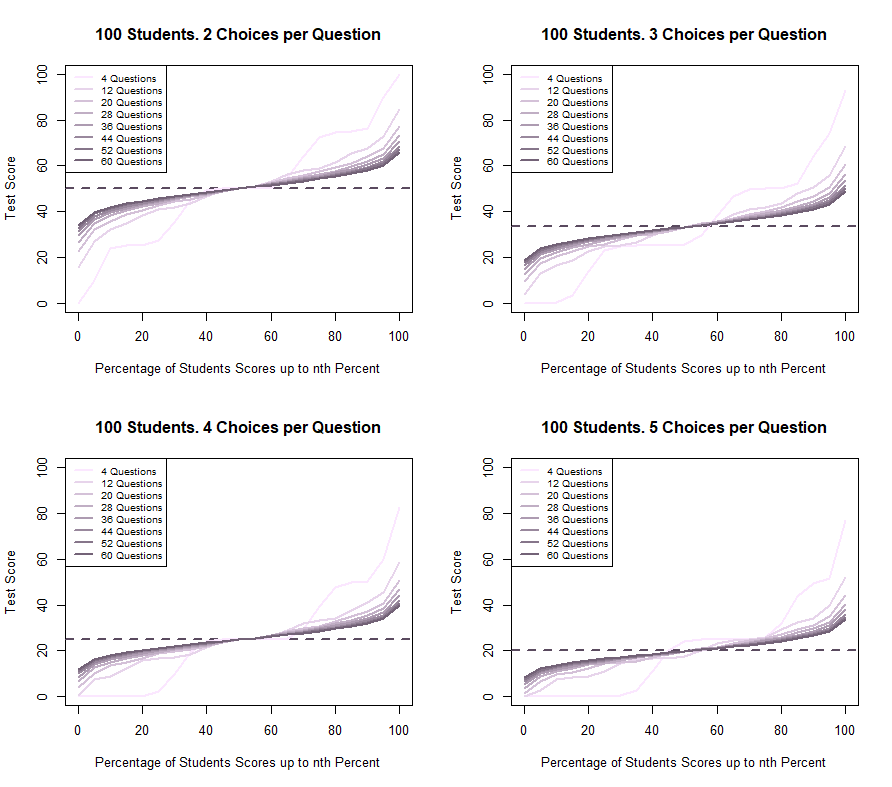

visualizing this through plots and a statistics table from a monte carlo simulation provides a clearer understanding. the cumulative distribution of scores for randomly guessing students reveals the diminishing chance of achieving high scores as the number of questions increases.

cumulative scores distribution for students making random guesses in a multiple-choice exam with varying questions and choices.

in the simulation with 100 students answering questions with three choices, we observe the effect of the central limit theorem. the standard deviation decreases as the number of questions increases, reflecting the theorem's principle that larger sample sizes lead to sample means approximating a normal distribution.

here's a summary table based on the simulation:

| questions | min | 25% | median | 75% | max | mean | sd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 0.00 | 22.87 | 25.77 | 49.98 | 92.96 | 33.29 | 23.52 |

| 12 | 3.90 | 24.73 | 33.25 | 41.87 | 68.67 | 33.34 | 13.57 |

| 20 | 9.30 | 25.80 | 33.28 | 40.12 | 60.60 | 33.32 | 10.50 |

| 28 | 12.57 | 27.41 | 32.99 | 39.21 | 56.39 | 33.35 | 8.89 |

| 36 | 14.77 | 27.97 | 33.20 | 38.47 | 53.65 | 33.31 | 7.84 |

| 44 | 16.42 | 28.56 | 33.23 | 38.01 | 51.63 | 33.33 | 7.09 |

| 52 | 17.64 | 28.91 | 33.21 | 37.63 | 50.18 | 33.33 | 6.53 |

| 60 | 18.73 | 29.24 | 33.24 | 37.33 | 48.92 | 33.33 | 6.06 |

these monte carlo estimates suggest that designing exams with the central limit theorem in mind can distinguish the probabilities of higher scores between students who guess randomly and those who study sufficiently. teachers can leverage this phenomenon to adjust exam difficulty levels and reward students who invest time in preparation.

whether you're a student or a teacher, understanding these dynamics can guide exam preparation strategies and improve the overall learning experience. so, study well, but remember, sometimes, a strategic guess can make a difference!